Welcoming Guests - Kol Nidre 5779

25/10/2018 10:00:48 AM

Rabbi Shoshana Kaminsky

| Author | |

| Date Added | |

| Automatically create summary | |

| Summary |

On Rosh Hashanah, I began a series of sermons on the five values that are a part of Beit Shalom’s mission. At those two services, I spoke about chesed–grace, and also Torah. This evening, I want to talk with about hachnasat orchim.

First, a Hebrew lesson. The word hachnasat comes from the word “to enter.” The meaning of Hebrew verbs changes depending on what conjugation pattern is applied. Hachnasat uses the hif’il pattern of conjugation, which makes the verb causal–meaning, causing someone else to do something. So the word katav means “he wrote” and the word hikhtiv means “he dictated.” Hachnasat means “to cause to enter,” and orchim means “guests.” To practice hachnasat orchim is to cause guests to enter—into our homes and our hearts.

Many of us make inviting guests part of our weekly or monthly schedule, but Judaism has turned the action into a mitzvah. As with the giving of tzedakah, welcoming guests is not only a nice thing to do, it’s actually a religious obligation. The Talmud tells us, “Welcoming guests is a greater action than welcoming the presence of the Shekhinah, as it says in the Torah: “He said, “my lords, if I have found favour in your eyes, please do not turn away from your servant.”

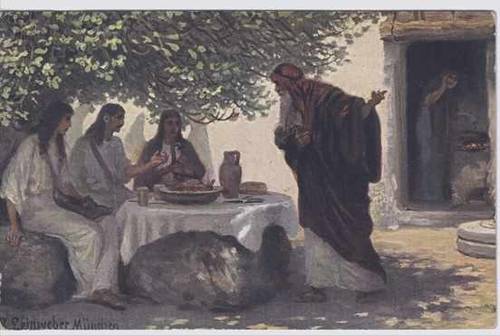

The quote here is from Abraham in chapter 18 of the book of Genesis. It is this story which sets up the model for what true hospitality looks like. When we meet Abraham at the start of the chapter, he is sitting at the entrance of his tent in the heat of the day. A different source suggests that he sits at the entrance of the tent specifically to spot travellers in need of hospitality, but here the rabbis understand that he is also recovering from his circumcision, which only happened at the end of the previous chapter. Presumably, he is not at his best. And yet, when he spots three angels disguised as dirty, dusty strangers, he leaps onto his feet and goes to work. Never has a 99-year-old man moved so quickly. He races from one tent to the next, organising food for his company. He begs them to stay, offering to wash their feet, and plying them with freshly-killed lamb and newly-baked bread. And all of this before he even asks their names.

The rabbis pondered many times over why God plucked Abraham from obscurity and chose him to be the father of the Jewish people. This story provides as good an insight as any into his generous and genuine character. There is so much that is extraordinary in this episode. Abraham rises far above and beyond what we might think of as the call of duty to look after people he has never met. Surely it would have been acceptable for him to say, “I’m not well today. I believe that my neighbour a few hills over can look after you.” But he didn’t say that. He welcomed in the strangers and completely spoiled them.

Of course, we know how the story ends: these men turn out to be angels bearing a thrilling message for Abraham and Sarah–that in a year, they will have a son. But it is important that Abraham does not know the identity of these men. We get the sense that this is how he treats each and every person who happens upon his tent.

Of course, it would have been far easier for Abraham living a nomadic lifestyle in a sparsely populated land. Nowadays, it is rare that we take a complete stranger into our homes. Rare, but not unheard of: each year in the weeks, days and sometimes even hours before the first seder, the office receives calls from the strangers in our midst. They may be overseas students, people here on business from interstate or overseas, and the occasional tourist. I have never had difficulty finding a seder table where they will be made to feel welcome. It helps that it says right there in the haggadah “Let all who are hungry come and eat.”

But hachnasat orchim is not a once-a-year mitzvah. Ideally, it’s a mitzvah for every Shabbat, or at least every festival. I note that nowhere in the texts I’ve checked is there a requirement that you offer your guests a gourmet five-course dinner appropriate for Master Chef. We all do the best we can–me most of all. My slow cooker is my friend, and whenever anyone asks, “What can I bring?” the answer is never, “Oh–you don’t need to bring anything.” I bake and freeze stuff, and I’m definitely not above taking advantage of the local bakery or pizza parlor to feed guests. Because it’s not actually about the food–it’s about the welcome we extend. I have a wild mix of crockery, used furniture, and a humble home which I am keen to open up to many more guests in the coming year, just as soon as my new puppy gets a little more used to strangers.

Rabbi Yosi son of Yochanan is quoted as saying, “Let your house be open to the winds, and make the poor members of your household.” The rabbinic work Avot d’Rabbi Natan expands on this idea by speaking of Job, who tradition tells us had entry-ways to his home facing north, south, east and west so that all who passed by would find their way inside. In my years as a rabbi, I have been present at many funeral meetings in which adult children have said fondly of their mothers, “her house was always open and full of kids from the neighbourhood.” Some of these mums had home-baked cookies and slices waiting to feed the hungry hoards. Others just opened a packet and a carton of milk. What the kids remembered was the open door–not the quality of the food they were fed.

I note that hachnasat orchim is not only about entertaining the people who are already your friends. It’s about opening up your home to people you don’t know well or barely know at all. I specifically chose this night to talk about this subject, because tonight is the night when you are most likely to be surrounded by people you don’t know. With us this evening are exchange students and tourists, newly-minted Jews and people who have recently relocated to Adelaide. With us as well are longtime Beit Shalom members that you may not have seen in quite a while, but are no less worthy of a warm welcome and a dinner invite.

I started thinking about giving a sermon on hachnasat orchim when a colleague of mine posted on a Facebook page that her congregants believed this to be a mitzvah that only the rabbi needed to worry about. She even had someone approach her and say, “It’s amazing that you manage to put on a dinner party every week,” to which she said, somewhat perplexed, “You mean–Shabbat?!” I’m delighted that this is not that kind of community. We have a wonderful tradition of hachnasat orchim at Beit Shalom—so much so that Alison Marcus’ challah–dearly missed!–and Merrilyn Ades’ creme caramel are legendary enough to have both become fixtures of Purim shpiel scripts. But both Alison and Merrilyn are known above all for the warmth of the welcome they extend. Others in our community have also been incredibly generous in hosting out-of-town visitors and guests at their homes. I hope that everyone who is here tonight will consider extending their hands in friendship as well.

Practicing the mitzvah of hachnasat orchim is often its own reward. I have gained friends, learned amazing things and added to my professional networks as a direct result of welcoming people I didn’t know particularly well into my home. I have carved the smile lines more deeply into my face as a result of all the laughter, and occasionally been present for extraordinary moments of connection. It is in no way an exaggeration to say that it’s all been an absolute pleasure.

On this night when we’re called to stand back and a take a long look not only at our lives but at the world beyond, I’d like to digress for a moment and talk about the global value of hachnasat orchim. We live in an era when countries are less and less willing to extend a hand of welcome. It is increasingly difficult to pick up and start a new life in a new country. Australia is no exception. Decades ago, the spouses of Australian citizens were automatically entitled to begin applying for citizenship as soon as they arrived. Today, a partner visa costs $7000, and the application process can last years. The answer to one of the questions on my citizenship exam was that a benefit of Australian citizenship is the ability to sponsor family members to come here to live. But if you visit the Department of Home Affairs website, you will see that there is a quota on how many such visas are issued each year, and as a result family members might have to wait years or even decades for approval. It seems to me that if these are both rights of Australian citizenship, the least the government can do is to extend the hand of hospitality to our family members whom we choose to bring to this country.

And then there is the issue of refugees. According to the UNHCR, more than 68 million people worldwide have fled their homes and are in need of care and protection. 40 million of those are internally displaced within their home countries, but 28 million more are living in a country not their own. We know that Australia is far from the only nation that has closed its doors to all but a trickle of refugees. In fact, it seems the world’s unwillingness to be open and welcoming to the most vulnerable has increased in direct proportion to the numbers of those needing refuge. It is not a far jump from the concept of welcoming guests to hachnasat hager—welcoming the stranger. As it says in Pirkei Avot, we are not expected to complete the work, but that does not mean we are free to ignore it entirely. We should seek to be part of the solution, rather than the problem.

Over the next twenty-four hours, we’ll spend a lot of time contemplating how we will try to be better in the year ahead. Hachnasat orchim—welcoming guests—is really not that difficult in the great scheme of things. And it has profound benefits, not only for us individually, but for us as a community as well. I wish you well over the fast, and may this new year be filled with joy, good health, and new connections and friendships as well. Shana tova!

Fri, 7 November 2025

16 Cheshvan 5786

News

The latest news from Beit Shalom

On the 80th Anniversary of the Holocaust - Andrews story.

Saturday, Feb 1 11:53amRenovations Report

Monday, Dec 9 10:38am

Upcoming Events

You must be logged in to see member events in our Calendar

-

Friday ,

NovNovember 21 , 2025Social Dinner

Friday, Nov 21st 6:30p to 9:00p

Bring a (generous) plate to share of vegetarian food or dessert

Privacy Settings | Privacy Policy | Member Terms

©2025 All rights reserved. Find out more about ShulCloud